If you are depressed, then you have hit the right page. Here is a detailed guide for folks who are depressed. The blog covers everything you need to understand and deal with your mental illness.

I often get letters from individuals who are depressed asking me what they should do. If you go on sites like WebMD, they will tell you that depression is a serious medical condition and that you should consult with your doctor. As such, I will assume you have already heard that piece of advice. Here, I attempt to offer folks something more.

What follows is a 15-stept blog series that I have developed to serve as a guide for folks who are feeling depressed or who think they might be and are wondering what to do about it. It is written mostly from a “self-help” perspective. You do not need to be in therapy (*although please see note at the end of this post). It is probably best suited for folks in the mild-to-moderate range of “clinical depression” and who have enough “mental energy” to read and think things through.

It does not try to sell you anything, although it does recommend several books you might consider. It also does not promise you a “quick and easy cure.” It is a guide that is divided into two broad parts. The first half of the series attempts to help you first understand what depression is, and use that to connect with understanding your situation and who you are as a person. Once we go through the steps of understanding depression and how it fits for what is going on with you, then the second half moves on to explore principles of “adaptive living.”

Related: Why We Need To Be Curious About Mental Illness

These are the guides for doing things differently in the areas:

One way to think of it is as a series of encounters that build on each other. Please proceed through them at your own pace. The first set of steps can be engaged quickly. The principles, however, require a much longer time to fully digest and implement. Part of the reason for the length is that finding one’s way out of a “depressive cave” takes time (i.e., usually weeks, often months). This is because climbing out of a depressive cave usually involves learning new ideas and skills, which need to be repeated and practiced.

The posts in the front half of the series are focused primarily on helping you identify the “neighborhood” of depression in which you are located. They involve learning about depression, about your life, and fostering understanding of your situation. The back half of the series focuses more directly on active steps you might take to move out of that neighborhood and into a more fulfilling place. The working assumption, supported by research evidence, is that it is possible for folks to find their way out of the cave of depression. It is, however, hard and takes effort and an adaptive attitude.

Although this blog series has many episodes, it does have a primary take-home message. It is as follows:

Depression is a state of behavioral shutdown that can happen for a host of reasons. The key thing to understand is that, as a state of behavioral shutdown, depression traps people into vicious cycles of avoidance and withdrawal. This means that you need to:

- Learn about the cycles of behavioral shutdown.

- Understand how they trap you, given who you are and the kinds of things that are driving your depression.

- Learn how to engage the world in a different way (i.e., doing, thinking, feeling, and relating).

Understanding what is going on and making these changes are hard to do. However, if you are patient and persevere, and are able to find a path of positive investment that nourishes your soul, then shutdown will reverse itself.

How does one find a path to positive investment? To guide the process we will be using the three “A’s”

Awareness involves increasing your understanding about what it going on, especially in terms of your feelings, thoughts, actions, and relationships. Acceptance involves being able to hold and tolerate negative feelings and distressing situations in a measured and mindful way. Active change means trying new things, even when it is hard. We will be considering each “A” in various ways in this journey.

Related: How Changing Your Beliefs Will Make You Realize How Much Life Has To Offer

As such, this journey invites you to adopt the attitude that you are attempting to:

- Increase your awareness of who you are and of what depression is, where it comes from, and what might be done

- Work toward increasing your capacity for acceptance of what is, including painful feelings and past losses

- Increase your engagement with things, even if your first instinct is to avoid and withdraw

What To Do If You Are Depressed: A 15-Step Guide

Step 1: Realize That You Are Not Alone

We can start with a general point of awareness that is important for not just people who are depressed but for everyone in society. Depression is common. It affects people across all social groups and classes. Consider that the World Health Organization identifies depression as the single most detrimental medical-health condition of all (including cancer or heart disease in terms of its “global burden”).

There are three key points for this first step. The first is that almost everyone is affected by depression, either directly or indirectly. As such, it is crucial that we are aware of this and create a community that is aware of this. Second, it is crucial that individuals dealing with depression know that they are not alone. The experience of profound loneliness is common in depression and, as we will see, it can contribute significantly to depressive states. However, the fact of the matter is that it is something many people deal with.

Third, I hope this insight might provide you with some notions about what you can do. For example, perhaps you could join a support group, either in person or online. If you Google “depression support groups” you might find something helpful there.

Related: Jin Shin Jyutsu: Ancient Japanese Technique For Stress Relief

Emphasizing the relationship aspect brings us to one of the themes for this series, which is the attitude of “loving compassion.” This means having a deep respect for the dignity for all persons—one’s self and others—and offering the general wish that folks flourish rather than suffer. As such, I would like to end this first entry with a “metta mantra” from the Buddhist Thích Nhất Hạnh:

May I be peaceful, happy, and light in body and spirit. May I be safe and free from injury. May I be free from anger, afflictions, fear, and anxiety.

May I learn to look at myself with the eyes of understanding and love. May I be able to recognize and touch the seeds of joy and happiness in myself. May I learn to identify and see the sources of anger, craving, and delusion in myself.

May I know how to nourish the seeds of joy in myself every day. May I be able to live fresh, solid, and free. May I be free from attachment and aversion, but not indifferent.

Love is not just the intention to love, but the capacity to reduce suffering, and offer peace and happiness. The practice of love increases our forbearance, our capacity to be patient and embrace difficulties and pain. Forbearance does mean that we try to suppress pain.

Related: Thich Nhat Hanh: The Art Of Letting Go and Why It Isn’t What You Think

This concludes Step 1.

Take-home” messages:

1) Depression is a state of shutdown;

(2) we need to find a path of positive investment that is nourishing;

(3) the process involves the three “As”: Awareness, Acceptance, and Active change.

Below is Step 2, which focuses on ways of relating to depression, with a focus on awareness and acceptance, rather than resistance and conflict.

Step 2: Turn And Look At The Beast Rather Than Fight It Or Run From It

Let’s face it, depression sucks. It feels miserable, it drains one’s motivation, and it orients people to want to escape and withdraw into an inner cave. Unfortunately, withdrawal into the cave has the ironic consequence of “feeding the beast.” Because of this, we need to develop a frame that orients toward the beast, at least somewhat. That is, rather than trying to hide in the cave or trying to publicly “smile” through one’s depression, the advice I offer is to look squarely at what is going on.

A metaphor from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) might help. Imagine yourself currently in a tug of war with the “beast” of depression. On one side is you, on the other is the beast, and between the two of you is a nasty pit. You are trying to pull the beast into the pit and be rid of him. He is trying to pull you into the pit. You are trapped in an epic struggle.

Related: 6 Concrete Ways To Improve Your Emotional Health

I am asking that you let go of the rope and simply look over at the beast standing there. Of course, doing so does not kill the beast. It is still there with you. But it also means you are not immediately fighting with it, trying to force it away. Remember, you are not alone: Imagine there are lots of people in lots of tug of wars with their beasts. Now imagine everyone letting go of the rope and then sharing with each other the fact that they have been engaged in a struggle.

The main point here is that we are shifting our attitude. Our step in this episode is to stop with a frontal assault that involves directly fighting, escaping, or trying to bury the beast that is depressed. Rather, it is about looking at it.

And, yes, in part that means living with it. This may feel scary and might well seem to be the exact opposite of what your instincts have been telling you: “After all,” you may be thinking, “I just want to be happy!”

That is understandable. But what we are starting on are the lessons of awareness and acceptance. They are not easy lessons. Finally, although you may feel alone in your cave, recall that you are not. Depression is something that, directly or indirectly, affects us all. We all need to pull together and help each other reverse the cycles of shutting down.

Related: How Changing Your Beliefs Will Make You Realize How Much Life Has To Offer

The message of Steop 2 is to reframe our initial way of relating to depression. Many struggles to fight against it. This post invites you to at least consider letting go of that direct struggle for the time being and allow yourself to accept the situation and the feelings you are dealing with.

A great Buddhist insight is that suffering is the combination of pain and resistance.

I invite you to move from resistance to a mode of greater acceptance. The next few steps in our journey are designed to help you further understand the kind of beast you are dealing with.

Let’s move on to Step 3, which is more about awareness, through understanding the “nature of the beast” which is depression, which was introduced in step 1.

Step 3: Recognize That Depression Is A State Of Behavioral Shutdown

Although depression is a common health condition, there is much confusion about what the term means. The goal in this part of the blog is to help you become clearer about what depression is. First, depression is different from “normal” grief or sadness. As this blog notes, when my dog died I was sad, but I was not depressed. Many people who are depressed don’t feel sad but may feel numb or angry or anxious and agitated.

Another area of confusion that people often get hung up on is whether depression:

1. Is a normal reaction to difficulty and loss

2. Arises because someone is being weak or having other limitations of “character”

3. Is a disease of the brain (i.e., a “chemical imbalance”) that has little or nothing to do with psychology.

Although these issues are important (and we address them in various ways in this series), they are not the best place to start when trying to understand what depression is.

Rather we need to start with a description of its most basic features. Descriptively, depression is a state of behavioral shutdown. Put in a common language, it means you feel like sht and don’t feel like doing sht. Why is this the case?

When someone is in a depressed state, there is a significant shift in the flow of mental energy away from the “positive emotional investment system” and into the “negative emotional investment system.” The positive emotional system is about being energized and open to new experiences, having a lot of curiosity and desires, and seeking and approaching “the good” (e.g., things that are emotionally nourishing like high-quality relationships, exploring interesting topics, and engaging in rewarding activities).

Related: 6 Concrete Ways To Improve Your Emotional Health

In contrast, the negative emotion system is about signaling danger and loss and avoiding and withdrawing into a defensive posture. Depression is a shift that pulls the positive emotion system down and jacks the negative emotion system up. That is people who are depressed experience increases in negative feelings like sadness, discouragement, despair, anxiety, irritability, anger, shame, and guilt. In addition, they experience less energy for engagement, exploration, pleasure, happiness, and interest. Technically, this is called “anhedonia.”

Depressed individuals also often experience fatigue, a focus on past losses, a discounting of future gains, difficulty concentrating, difficulty starting new activities, and problems with sleeping and eating. The pain is sometimes so great and the feeling of being trapped too intense that the person comes to believe that the only solution for escape is suicide.

Step 3a: Be Aware of the Two “Paradoxes” of Depression

How might this understanding help you?

First, it helps you label what is going on. For purposes of awareness, we want you to be able to make meaning out of your feelings and drives (or lack thereof). With the behavioural shutdown model, you can interpret your state of mind as a shift in your drive and psychic energy from the positive to the negative emotion system.

Second, it can help you become aware of what I call the “twin paradoxes” of depressive conditions. The first is the paradox of shutdown. This paradox refers to the fact that when you are depressed, your emotional instincts are telling you to withdraw, avoid, and retreat into a cave. But if you retreat into the cave, where does that leave you? It leaves you alone, feeling like crap, with no place to go.

This means something very important: Your instincts to escape and withdraw “paradoxically” feed the beast that is depression. This idea is key to this series. It is also key to understanding the neighbourhood of depression and how you have found yourself in it and how you might learn how to move out of it.

Third, this cycle of shutdown highlights that folks need to act and react differently than their depressive instincts tell them to act and react. But, unfortunately, as we consider this fact, we encounter another paradox of depression. As you likely know, depressive moods suck available energy from you. The last thing a depressed person has is the energy to invest in some long, drawn-out process.

We can label this the paradox of effort. To turn the cycles around, you need energy and work effort—but depressive shutdowns suck all the energy out of you. Thus, it is very hard to do what is needed.

Let me summarize this entry as follows:

Depression is, first and foremost, a state of behavioural shutdown.

This means that your energy shifts from the positive to the negative, and makes you feel like doing nothing. This results in two painful paradoxes of depression. The first is the paradox of shutdown. Your depressive instincts tell you to avoid and withdraw, but that only drives you into a cave, feeding the beast more and more.

The second is the paradox of effort, that significant effort and energy are required to not be driven into a cave, but depression saps all your energy from you.

These two paradoxes help explain why so many people fall into depressive caves. The solution to these paradoxes involves working to develop the right mindset, which in part involves pacing one’s self and being patient and focusing on moving ahead slowly and purposefully toward more valued states of being.

To help with this movement, I would like to introduce a new “attitude”. In Part I, we introduced the attitude of loving compassion for self and others. The attitude I would like to introduce here is the attitude of curiosity. Curiosity is an attitude of wonder, of learning, and of openness to ideas and to feel. A curious person tries to explore. She asks questions about what, why, how. Today’s entry was about answering some basic questions about what depression is, and how to understand some of its key “paradoxes”.

Related: Why We Need To Be Curious About Mental Illness

Thus, we can think of your willingness to read and understand this post to be in part driven by some inner curiosity. Although I know it is difficult when you are depressed, perhaps you can open yourself up to being a bit more curious about yourself, your depression, and related feelings, to others and what they are feeling, and your world across time (the past, present, and future).

We end today with a quote on the concept of curiosity from Albert Einstein:

The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery every day. Never lose a holy curiosity.

In the step 4, we turn our attention to things that drive folks into shutdown mode.

Step 4. Assess Your Level Of Depression

Let’s start by reflecting on the level of your depressive shutdown. We can do this by asking how much shutdown is present and for how long. We can think of this in terms of the intensity, duration, and frequency of the symptoms.

Put in the form of questions, we can ask: How strong are the symptoms? How long do they last? How often do they occur? Probably the easiest way to get a picture of your levels of depression is to take a brief test. Here is an easy test, the PHQ 9. Please take it and see how you score, as it gives you a sense of what level of depression you are dealing with.

Note that when you take it the meaning of your scores will depend on if you are a “minimizer” or “exaggerator”. This is hard to assess if you aren’t trained, just know that a “minimizer” tends to dismiss or downplay their symptoms and an “exaggerator” tends to overshoot. For now, just note that the correct interpretation depends on how you tend to respond, but it should give you a basic idea.

Related: 10 Reasons Why People Refuse to Talk to Therapists

In addition to noting your overall severity, please take a look at the symptoms you are dealing with. These are important because they can serve as clues for areas to focus on. For example, are you having problems with sleep? If so, that might be a pattern you think about addressing, as sleep habits are key to getting the rhythms of your biology flowing smoothly. Or, if you are having trouble with negative thoughts about yourself, then a cognitive approach that focuses on adaptive thinking might be more appropriate to focus on.

The second half of this series (starting with Part VII) will bring the focus more on the kinds of things you can work to change or do differently. Right now, we remain in the “awareness” stage, so just note your overall level of depressive symptoms and the more specific domains you are having problems with.

Now let’s review terms that mental health professionals use in considering this condition. This too falls under our process of “Awareness” and is consistent with the attitude of being curious.

Let’s start with the term “clinical depression.” Perhaps you have heard of it or of “clinically significant” symptoms. “Clinical” is a professional jargon term that just refers to depressive symptoms that are causing or are associated with significant distress and difficulty functioning. It is basically a judgment call that professionals make that indicates someone is experiencing problematic or substantial symptoms of depression that could be the focus of treatment.

Another key term is a “Major Depressive Episode” (MDE). Sometimes this is what is meant by clinical depression. An MDE is a term from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is what most professionals use as the official diagnostic codebook. An MDE is defined as the presence at least five of the nine symptoms that are listed on the PHQ 9. These symptoms need to be present most of the time for a period of at least two weeks. MDEs usually last several weeks into months.

If someone meets the criteria for an MDE, they often get diagnosed with a “Major Depressive Disorder”. One key piece of information to consider is your level of severity, which is usually described in terms of “mild”; “moderate”; or “severe”. Mild is where the person barely meets the criteria for an MDE.

Such folks often have a “smiling depression,” meaning that they can hide it from others and are not necessarily obviously depressed on the outside. That is, they can go to work and function in social settings, and don’t show any motor or other gross impairments. Note that the word “mild” here is not meant to suggest that it is not important or significant. It is, after all, part of the overall heading of a Major Depression.

A moderate MDD is when functional impairment starts to become obvious. Folks in this category frequently stop doing things like going to work (at least miss a day here or there), reduce time hanging with friends, or disengage from life in other ways. Concentration is hard, sleeping or eating is often disrupted, and anyone who has much contact with the person would likely notice a difference in how they are presenting.

Severe levels of MDD are profound cases of shutdown. Here the person can’t hide it at all. They move slowly, they talk slowly, their eating, sleeping, and pattern of functioning are often completely disrupted. It is hard to see someone in a severe MDD and not conclude they are “ill” in a medical/health sense. Sometimes you might hear this described as a “melancholic” depression (see here for a discussion of it and related terms).

We should also make the distinction between “recurrent” and “single” episodes. As the words sound, a single episode means this is the first and only time someone has been depressed. Recurrent (or chronic-recurrent) refers to folks who are dealing with repeated episodes or folks dealing with depression for years.

This distinction is important in part because it relates to prognosis. A single episode generally is easier to treat and more likely to result in folks bouncing back quickly. Why is this the case? Well, there is an old saying in neuropsychology that “neurons that fire together, wire together,” and it is likely that the more time one spends in a depressive state the more that state becomes accessible. In addition, the more one has been depressed, the more vulnerable one is to relapse.

Related: 3 Most Common Mental Health Disorders In Men

We should also be clear about the difference between “bipolar” and “unipolar” depression. Bipolar is the term that professionals use when an individual has experienced a “manic” or “hypomanic” episode in the past. These are episodes of heightened energy, positive or hyper-charged mood, a decreased need for sleep, irritability, excessive goal-oriented activity, increases in risky and impulsive behavior, and in full-blown episodes, disorganized thought, delusions, and hallucinations.

The presence of the bipolar disorder is crucial to know, as it requires different kinds of medications. In addition, there are good reasons to believe that bipolar disorders likely involve significant contributions from neurobiological breakdowns or malfunctions (i.e., I see bipolar conditions as more “disease-like” in its nature than unipolar). “Unipolar” are depressive conditions that do not involve a history of manic or hypomanic episodes.

Another key thing to be aware of is the notion of “persistent” or “trait-like” depressive presentations. If you recall Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh, you will be able to conjure up what it looks like when someone has persistent depressive symptoms. In the past, this was called “dysthymia” and before that, it was labeled a “depressive personality”. This tendency toward trait-like depression is related to the broader category of what professionals call “trait neuroticism.” This refers to a person’s natural tendency to experience negative emotions.

Step 4a: Assess your level of “trait neuroticism”

If one is high on the trait neuroticism then that is important to know, as it influences where one can expect to be in terms of one’s negative feelings, even when things are going reasonably well. That does not mean that you will be depressed all the time, as a depressive episode is a different state of being than just being high in trait neuroticism.

But it does mean you will be more likely to experience negative emotions and have a harder time being “calm” in stressful situations than others. And, as we will see, that is very important to understand, because we will need to help you learn to relate to your feelings in a healthy way.

As this blog notes, it is important to know if you are high in this trait. As we will see, learning to relate to your emotions is important, and doing so can be hard if you are high on trait neuroticism. [Please, note, however, your scores on this “trait” measure will likely be higher when you are depressed than not, so if you get out of your depressive episode, it might be helpful to take the assessment again.]

Finally, I need to make a comment about what mental health professionals call “co-morbid” conditions. Co-morbid means that the individual is dealing with more than one problem or illness, and they combine to make things especially complicated. If we consider that depression is a state of behavioral shutdown, then it makes sense that it often is secondary to many other problems. And, indeed, it is highly “co-morbid” with conditions like generalized or social anxiety, personality disorders, schizophrenia, substance misuse problems, and chronic illnesses or chronic pain. Of course, all of these difficulties relate to the things in a person’s life that might be driving the shutdown.

Related: Which Of the Five Psychological Factors Is Your Most Dominant? QUIZ

In sum, today in step 4 we focused on increasing your awareness of your depression. Specifically, we emphasized getting clear on how depressed you are by taking a screening measure, we identified some key mental health terms, and we introduced the concept of trait neuroticism and pointed to some resources for understanding that concept. This is all in the service of getting to know the beast that is depressed.

In step 5, we will continue the journey and start to map more clearly your personal struggle with depression—that is, we will start to map the various ways folks get depressed, which will then allow us to map who you are and put the puzzle pieces together.

Perhaps you are frustrated to hear this. Perhaps your reaction is, “I don’t need to learn any more technical stuff, I just want to stop feeling this way!” That makes sense and we should observe you’re having that thought with compassion. Yet in compassionately observing it, we should also note that the thought goes against two of our “A” principles that are guiding us on our journey. Recall those are the principles of Awareness and Acceptance. The thought echoes the wish for the third “A”, which is Active Change.

Please note that part of what we are learning on this journey is the process of being-in-the-world. The process of being-in-the-world refers to how one is in the world, rather than where one is. The old saying, “It is the journey, not the destination” makes a point about the process. The process of being that we are cultivating is a mindful attitude of awareness and acceptance.

This involves intellectual curiosity about the world, emotional curiosity about your feelings, and a way of being in a world that is aware and attuned to the present. It also involves patience and the capacity to tolerate distress (a key facet of acceptance).

Here, in step 5, we get curious about the kinds of things that might be driving your state of behavioral shutdown. Specifically, we learn about differences between: a) depressive reactions; b) depressive disorders; and c) depressive diseases.

Step 5: Recognize Depressive Reactions, Depressive Disorders, And Depressive Diseases

If depression is a state of behavioral shutdown, then it makes sense that we should ask, with an attitude of curiosity, “What might be causing my emotional-motivational system to shut down?” I distinguish between three broad kinds of causes and classify them in terms of

1) depressive reactions;

2) depressive disorders; and

3) depressive diseases.

Each of these domains can contribute to depressive feelings, and it is very important to understand what they are and why.

Depressive reactions refer to shutdowns that follow serious “psychological injuries,” such as the death of a loved one or other major losses, such as a divorce or job loss or other major life event that is experienced as a core life failure. Depressive reactions also include shutdown responses to brutally difficult or oppressive life situations, such as living with an abusive partner or dealing with chronic pain.

Our mood/emotional systems generally react to these kinds of brutal events with avoidance and withdrawal. The key questions for you here include: Can you identify a past injury that your system is reacting to in a way that the shutdown makes sense? Are you trapped or humiliated or experiencing chronic pain such that it feels that you have no path of escape? Have you experienced a loss or failure that you can’t let go? In one of my blog, with the odd sounding title: “How depressed do you want to be?”, I explain how this unusual-sounding question gets at a key feature of depressive feelings, which is that they can be understood to be a natural consequence to a brutal situation.

Related: Mental Health: The 10 Types of Sleep Disorders

Depressive disorders are the second class of causes that drive people into depressive caves. Depressive disorders involve “maladaptive” patterns of acting, reacting, relating, and coping with stress that actually makes things worse. These are vicious cycles that drive people into dead ends.

A vicious cycle involves the following:

(a) stressors or difficulties or losses in a person’s life cause them to

(b) adjust and cope in problematic ways, which lead to

(c) more trouble functioning and greater distress that then results in

(d) even more problematic coping.

This means the cycle feeds back on itself and results in things getting worse and worse. Consider, for example, the person that uses alcohol to escape from his emotional problems. Although alcohol might take the pain away in the short term, over time things often get worse and worse. Now recall the first and second “paradoxes” of depression. The paradox of shutdown results in emotional instincts to withdraw and avoid, but this drives people into the cave and “feeds the beast.”

The paradox of effort is that depression sucks energy from you that is needed to engage in the world and reverse the cycle. The basic question here is whether your depressive reactions to stress making things worse for you. Tomorrow, in Part VI, we will introduce the concept of “neurotic loops,” which is one of the most common vicious cycles that contribute to depressive disorders.

Depressive diseases are the third class of causes. This relates to biology. Before we describe depressive diseases, we need to reflect on some basic biological considerations about depression. In terms of general biological considerations, we need to be clear that depression is “biological” in the sense that a Major Depressive Episode really does represent a fundamental shift in your biology.

Related: 5 Tips to Help You Combat Depressive State of Mood in College

Changes happen in metabolism, arousal, stress reactivity, stress hormones, biorhythms, and many other domains in the body. This is one of the many reasons that asking depressed people to just “snap out it” is misguided; it is like telling a person who has not slept for 24 hours to just stop being tired.

Of course, almost everyone understands that feeling sleepy after being awake for a long time is not a disorder. Likewise, being depressed if one is being abused or trapped in vicious psychosocial cycles can also be seen as a natural consequence. Thus, just because it is “biological” does not mean that depression is a disease. And yet it is also the case that some people are tired because they have in fact have a sleeping disorder, such as sleep apnea.

Likewise, it seems plausible that some people have neuro-biological systems that are highly sensitive and become inflamed or reactive in ways that result in folks more easily tipping into depressive shutdowns. We know a number of conditions such as hypothyroidism and vascular strokes in the left hemisphere of the brain can result in folks becoming depressed.

In addition, chronic depression creates many biological sensitivities over time. I call conditions that seem driven by malfunctioning biology to be “depressive diseases.” I am especially likely to think in these terms when someone is dealing with severe or “melancholic” depressions.

Although the nature of “depression as a disease” remains controversial, many professionals and laypeople view it this way. In addition, many people report benefiting from anti-depressant medications. In addition, there are other brain-based interventions, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation, that have reasonably good evidence for chronic and treatment-resistant depression.

Related: 6 Antidepressant Medication Myths Debunked To Help Make Meaningful Choices

In my professional opinion, if you are dealing with moderate-to-severe levels of MDD, then, in addition to considering psychotherapy, you should consider consulting with a physician and testing out whether medications or other biologically based interventions might help.

How and if such medications help and if they do or do not result in side effects varies substantially from person to person. I consider it a bit like “mental alchemy.” That is, medical doctors can “sprinkle” meds on the nervous system and hope for the symptoms to reduce. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. I consider biological interventions one angle that needs to be considered in the context of the larger understanding of depression as a state of behavioral shutdown.

Today we learned more about the nature of depressive shutdowns. Specifically, we started to classify different things that can result in such shutdowns. We identified three broad classes of

1) reactions;

2) disorders and

3) diseases.

Depressive reactions refer to feelings that are a natural consequence of loss, difficulty, and failure. Understanding that there are depressive reactions allows you to ask yourself the strange-sounding question: How depressed do I want to be? The point being that our emotions and moods offer crucial information for our needs and goals and if our situation is brutal it makes sense that we would feel depressed.

Depressive disorders refer to a psychological condition where the way someone is responding to stress and acting, reacting and coping with their feelings and relationships are such that things get worse and worse in the form of vicious cycles. We also highlighted that biology plays a role both in general and some folks have symptoms that are severe enough and fail to respond to changes in the environment such that I think it is reasonable to label their conditions “depressive diseases” and to consider biological interventions.

Related: 13 Characteristics Of A Mentally Healthy Person

Earlier in this series, we noted that both professionals and laypeople are confused about depression. For a host of reasons, they get stuck debating whether we should think about depression as either a normal reaction, a psychological disorder, or a biological disease. Our behavioral shutdown model helps clarify how states of shutdown can emerge from the environment, from coping styles, and be connected to biology. Tomorrow, we return to the idea of depressive disorders and will explain one of the most common maladaptive cycles, that of a neurotic loop.

Finally, if you found today’s breakdown helpful, you might check out this blog, which uses this kind of logic to list 23 different “kinds” of depression. It might help you identify the nature of the beast that is your traveling companion.

Below is Step 6.

Step 6: Understand And Identify Neurotic Loops

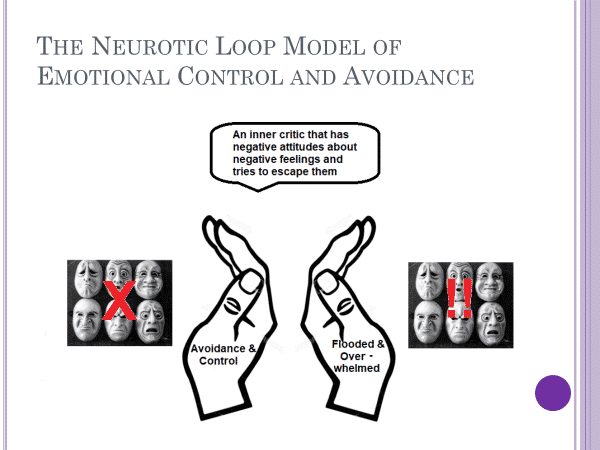

Neurotic loops develop when people have negative feelings about their negative feelings. Yes, you read that correctly. You have feelings about your feelings. Today we want to get clear about why this is so, and why it drives many people into depressive caves. (Note that they are called “neurotic” because although the person is trying to cope and control in an effort to make things better, the strategies often backfire and make things worse.

To begin, let me ask you a few questions about how you think about your feelings. Do you ever fear your depressed moods and fight against them (i.e., do you play tug of war with the beast, as was mentioned in Step 2)?;

Do you ask yourself questions like “Why can’t I just be happy?” or “What is wrong with me?”; Do you fear or feel uncomfortable with certain feelings, like being vulnerable or sad or angry? Do you criticize yourself for the feelings you do have? Do you try to suppress, avoid, deny or control your feelings? Are you sometimes overwhelmed by your feelings and feel flooded by them, even as you try to escape them? If you answered “yes” to these questions, then you may well be struggling with neurotic loops.

What exactly is a neurotic loop?

It is when folks get into a battle with their feelings that leaves them depleted, stressed, and feeling even more critical about themselves. Such loops usually involve three things.

The first is a “neurotic temperament.”

As was described in Part IV, this refers to the “set point” of the negative emotion system. It relates to how sensitive you feel, how strongly you react to negative events, and how long it takes you after a stressor to return to baseline.

The second primary ingredient is the stressors you face, relative to your felt sense of security.

This refers to the real-life problems in living that threaten your core needs and leave you feeling insecure and psychologically “malnourished”. Key psychological needs include the need for safety (which is violated when folks are traumatized), the need to be connected to and valued by important others, the need for achievement and competence, the need for crucial resources (i.e., money and shelter), and the need for play, growth, and exploration.

The third ingredient relates to how folks cope and react to their feelings in these stressful and psychologically difficult circumstances.

When those secondary reactions are negative and controlling in regards to the primary feeling, then folks can find themselves in a neurotic loop.

To see what I mean, let us imagine Julie as someone who deals with depression and social anxiety and who was invited to a social gathering and gets up the courage to go (see here for a blog on social anxiety). Ten minutes into the party, she has what she feels to be an awkward conversation. Moving to an isolated part of the room and trying to look casual on the outside, she internally launches in on herself: “What is wrong with you? Why are you so sensitive? This is so easy for everyone else. You can’t even come to a gathering for ten minutes without screwing things up.”

To help understand what is going on, we can divide Julie’s mental experience into three separate but related domains. One domain is her “emotional-experiential self.” This is her nonverbal “feeling mind” that automatically tracks what is going on and directly connects her to her body. I often call this the “heart.” Julie has a “sensitive” heart relative to other people, which is the sensitive way of saying she has a neurotic temperament.

The second domain of mind is her “narrator.” This is the inner talking part of her consciousness that explains what is happening and why, and how she should be. This is the part that privately criticized her for her weakness. Finally, there is Julie’s “public self.” This is the public presentation she offers to others (the part that tries to look casual, even as she is boiling inside). The relationship between these three domains of the human mind is key to understanding much about mental health.

Internal neurotic loops involve the relationship between the domains of “the heart” and “the narrator.” To understand why these domains of mind are often in conflict, we need to recognize that they operate in very different ways. The feeling mind or heart is quite automatic, fast and reactive. It feels things based on what it perceives relative to its goals in the immediate situation. If it perceives potential threats, it will send out alarms and result in general a feeling of worry or concern and will orient toward possible bad things happening.

The narrative mind is more complicated. It not only thinks about what is happening, but it also can narrate thoughts about what ought to be. This means that when the narrator is oriented toward the heart, it can decide whether the heart is feeling the “right thing” or not. This means that if the narrator decides the heart is not feeling what it should or if it decides the feelings are dangerous, then it will become critical and controlling and try to avoid or deny the feelings.

Where does the narrator get the ideas for what an individual ought to feel? Originally, these notions come from other people, either directly or indirectly. We learn rules and roles and what we should do and feel from our families and friends growing up.

For example, it is likely that you received messages about whether or not it was “okay” to be shy or angry or vulnerable. Because people generally want to be liked and accepted, they turn those judgments onto themselves. That is, the narrator internalizes (or takes over) the real or imagined judgments of others and then tries to control the heart, often by being critical or punitive.

So what does this mean for your mental health?

To understand why this inner conflict can be such a big deal, I have folks engage in what I call the “restaurant exercise.” Here is how it works. Imagine yourself at one of those big-city crowded restaurants where folks have tables very close to each other. Now imagine yourself at one table and next to you is an adult talking to a child.

The adult represents the critical narrator that is having negative reactions to the heart, which is represented by the child. Now imagine that you overhear what the adult says to the child. To see this, we can use what Julie said to herself as an example. That is, imagine an angry, critical adult harshly saying the following to a vulnerable child: What is wrong with you? Why are you so sensitive? This is so easy for everyone else. You can’t even come to a gathering for ten minutes without screwing things up.

What do you think happens to the child?

We can be sure of one thing. The child will not respond by “snapping out of it” and thanking her mother and being more secure. Instead, the child will either shrink and submit or throw a temper tantrum.

Neurotic loops stem from this kind of “inner family conflict” playing out in your head. It is a battle between the judgmental narrator and the vulnerable heart. It is a vicious cycle because it feeds back on itself. Even if the child says “Ok, I will be quiet,” the heart is still hurting and likely is hurting even more after being criticized. Not uncommonly, there is tension and a buildup and eventually, the child/heart will “lose it.”

When that happens, negative emotions flood the system and the person becomes filled with depressive despair or rage or panic in a very painful and dysregulated and maladaptive way. Of course, if this happens it only proves to the narrator that the heart/inner child needs to be controlled. This means that the cycle gets more and more entrenched.

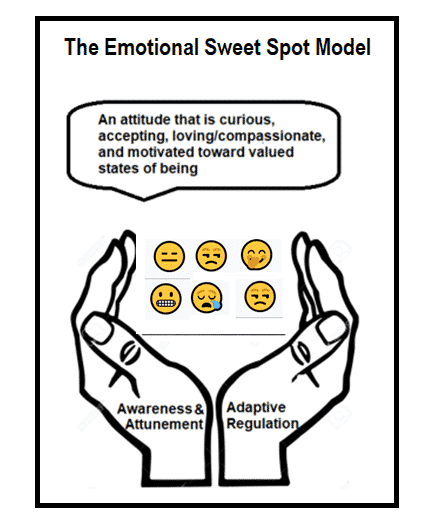

Here is a diagram I use to illustrate neurotic loops. It represents the fact that primary emotions are blocked and the narrator has a critical and controlling attitude. Sometimes, however, the emotional heart spins out of control and the person is flooded in a painful and powerful way.

Today, in Part VI, we covered the idea of neurotic loops. It involves the fact that we have three domains of mind: 1) the heart (or feeling mind); 2) the head (or inner narrator); and 3) the public self. Neurotic loops are states of inner conflict between the heart and the head (which often occur in order to manage the real or imagined judgments from others).

The task for today is to wonder whether or not you have negative reactions to negative feelings. If you answer yes, and that you often feel very differently than you wish you felt, then that is a crucial piece of information for understanding your depression. For now, just allow yourself to become aware of the fact that you have feelings and then secondary thoughts and feelings about those primary feelings.

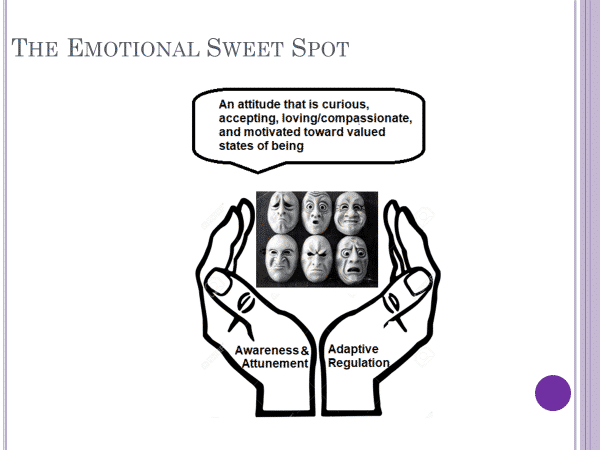

Later, in the back half of this series, we will be exploring different ways for you to relate to your primary feelings and examine how to be aware and attuned to your feelings on the one hand and learn to adaptively regulate them on the other. Here is a diagram to give you a sense of where we are headed.

Our journey of awareness and acceptance continues tomorrow. Our focus will shift a bit and we will broaden the picture. Specifically, we will start to get a better understanding of your overall psychological well-being, your self-concept, and your strengths. These pieces are key contexts in which to place your depressive feelings.

Here is the next blog in the series (Step 7).

Step 7: Understand Psychological Well-Being And Its Relationship To Depression

The reason is that to understand your depression, you not only need to look at it through the lens of behavioral shutdown, but rather we need to consider the whole of your psychological functioning. By understanding the broader picture of your life, you will be in a better position to recognize the things that might be contributing to your behavioral shutdown and things you can do to find psychological nourishment and pathways toward positive investment.

What is psychological well-being?

A good short description was given by the philosopher Immanuel Kant, who described it as “happiness with the worthiness to be happy.”

As this definition suggests, well-being is made up of subjective feelings of satisfaction, contentment and joy (and the relative absence of suffering) coupled with a judgment that such feelings are “worthy” of that happiness. Worth here is generally determined by taking an objective look at the person’s life and evaluating it in terms of functional and moral standards.

For our purposes, if you are engaged in a constructive life and feel good about it, then you have high well-being. However, if you feel you are failing and are not at all being productive in a meaningful way and are having difficulties functioning and are miserable about it, then you have low well-being.

As this description suggests, depression is definitely related to well-being. Generally speaking, if someone is high in depression, they will be low in psychological well-being. However, the point of this blog is to help you see that these two concepts are definitely not the same, and it is important that you have clear notions about both of them.

Some people struggle with depression even as they report relatively high levels of well-being in other areas. For example, the famous psychologist Jordan Peterson has reported that he struggles with depression. I don’t know him personally, but I could imagine he might be someone who also feels he has high well-being, perhaps even if he feels depressed. In addition, there are also some people who have low psychological well-being but are not depressed.

The bottom line is that the two concepts are related, but they are also different in important ways. And it is important for folks who are depressed to think about their well-being and to understand where they are in their well-being and how the two are (or are not) related in their lives.

Related: 7 Tips To Create Instant Well-Being On A Really Busy Day

Step 7a: Assess your well-being and reflect on it in relationship to your depression

The basic way to assess well-being is to ask how you feel like you are functioning in key domains and how satisfied you are with your life, both overall and in specific domains. The “overall” is the assessment someone makes when they are asked how their life is going in general.

Then we look at more specific domains of functioning. For example, how is your biological health and fitness? Are you free from major illness and injury? Are you able to exercise and feel comfortable and confident in your body? Or do you struggle with pain or other health-related problems?

Another key area refers to how you are doing psychologically “on the inside.” This relates to your sense of emotional health, your levels of self-acceptance and your sense of autonomy. Folks who struggle with neurotic loops report low emotional health and low levels of self-acceptance. Autonomy is the sense that you are free from others and can determine your own life.

We can then look more at how you are doing in relationship to your environment. Relationships with others are really key. Do you have high-quality relations with others, or are you alone and isolated? Have you lost cherished relationships? Also crucial is how you are doing at school or in your job or career? And do you have the mental and material resources to control your environment enough to feel secure or does it feel like life is overwhelming you and you can’t cope with all the stressors that are coming at you?

Finally, there is your higher-order sense of being. Do you feel like you are growing and learning? Do you feel like you are developing in a positive direction? And are you able to make deep meaning out of your life? Do you have a philosophy of living or a spiritual sense of your place in the universe that helps guide you? Or are you experiencing a crisis of meaning and perhaps feel that nothing matters?

The point of these questions is to get you seeing the connection (or not) between these domains and your depressive condition. To help advance this understanding, here is a link to a blog that gives you a quick assessment of your overall well-being.

It covers the following 10 areas:

1) Overall life satisfaction;

2) Mastery and control over environment;

3) Emotional health;

4) Relationships;

5) Autonomy;

6) Self-acceptance;

7) Academic (or occupational) functioning;

8) Health and Fitness;

9) Meaning and Purpose; and

10) Personal Growth.

By taking it, you can see where you fall overall, and you can see if there are some domains of functioning and nourishment that are likely connected to your feeling depressed.

As we did in Part IV when we had you take the assessment and reflect on your symptoms, notice the pattern of your scores, relative to your overall score. Specifically, note if there are some areas that you are doing better than in others. How does your overall life satisfaction correspond with your levels of depression? If you score very low on the overall measure (i.e., in adding all the scores, you were below a 30), then it is likely that your depression is tied up with your general living circumstances and how you currently feel about, well, everything.

Related: Ryff’s Model of Psychological Well-being: How Happy Are You?

That is a different profile than someone who is happier overall and has good relationships and good functioning at work or school but struggles deeply with self-acceptance and emotional health. Or maybe you score in the somewhat high range on most domains, but very low on meaning and personal growth. That would say that you feel stuck and are struggling whether your life has the sense of meaning you sense it might (or you are struggling with nihilism, which means the sense that your life is meaningless).

The take-home message for today’s blog is to shift the focus from understanding depression to understanding psychological well-being. The two are related in that as one’s depression gets worse, psychological well-being will inevitably go down. However, the two concepts are not the same.

As we know from this series, depression is a state of behavioral shutdown, where one’s positive mental energy shifts toward the negative. As we have learned today, well-being is about being happy and functioning well in the world across a number of key domains and having a sense of purpose and connection to others. By engaging in a self-assessment you can start to wonder about the relationship between your depression and your well-being. This can perhaps open up new possibilities to guide you, especially when we shift into ideas where you engage in more active change strategies.

This concludes the first half of the series. The next installment (step 8) can be found below. In it, we move to the back half, where our primary focus shifts from Awareness and Acceptance to more Active change principles.

By Active Change, I mean that we are ready to cultivate the part of you that is looking to do something different. Perhaps you might be able to say something like:

“What I have been doing has not been working great for me. For the benefit of my future self, I am willing to try some new things. It will take time and effort, and the effects will not necessarily be immediate. But if I effectively orient myself toward learning and growing and seeking and approaching ‘the good’ rather than avoiding, defending and withdrawing from ‘the bad,’ then I will significantly increase the likelihood I will find a path out of the darkness.”

Step 8 – Values Clarification

To begin this part 8 of the series, we start with a well-known concept in psychotherapy called the stages of change perspective. This refers to the idea that, when it comes to making active changes in their lives, people operate in very different spaces.

Stages of change

Specifically, five different stages of change have been identified. They are:

1. Precontemplative, which means the person is not even conscious of there being a problem and thus is in no place to take steps to change anything;

2. Contemplative, which means that the person is aware that there is a problem and is thinking about doing something, but has not committed;

3. Preparation, which means that the person is getting ready to act;

4. Action, which is when the person is actually trying to do things differently;

5. Maintenance, which is when the person is working to maintain goals at the new, more adaptive level of functioning. When and if someone relapses, they might then return to an earlier phase in the cycle.

By clicking on these blogs, you have demonstrated that you are (at least) in the contemplative stage. And if you have followed along and were waiting for us to get to the Active change stage, then you are in the “preparation” phase. Maybe you have even engaged in some additional reflections from the blogs. For example, if you have tried to internalize things like curiosity and acceptance after reading the blogs, then you already have engaged in some action.

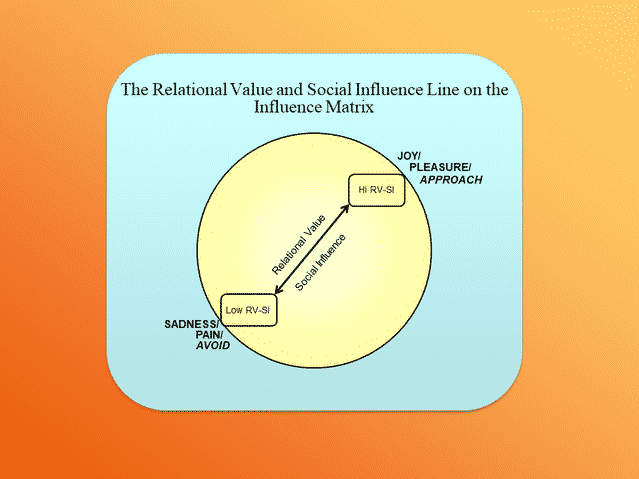

And that is where we are now in the series. We are getting ready to explicitly make the jump into action. The frame that we will be using to guide our general approach is what I call the “adaptive living equation.” As this blog notes, the adaptive living equation means that you realistically try to maximize valued states of being, given who you are and the situation you find yourself in.

Related: Toxic Core Beliefs: 9 Ways To Transmute Them

What do I mean by “valued states of being”? Valued states of being referred to your desired outcomes in the short and long term, based on what you value and your overall situation. Put in the form of a question: Given your values, how would you want to handle the current situation, and what are your desired outcomes in the short term and over the long term?

Here we can build off of our idea of depressive disorders as often stemming from maladaptive patterns of the shutdown. In contrast to adaptive living, maladaptive living refers to ways of being that result in distress and dysfunction and move us away from valued states of being. As we know from our blog series, because of its paradox of shutdown and paradox of effort, depression often gets folks trapped into maladaptive cycles.

As has been discussed, this cycle often involves: (a) an individual who feels highly stressed and vulnerable who (b) hates feeling that way, and (c) is in a stressful situation that elicits negative feelings which (d) causes them to avoid and withdraw which results in them (e) doing less and less (i.e., shutting down) and (f) feeling worse and worse, completing the cycle. Given this, the key is to break the cycle of avoidance, withdrawal, and shutdown, and to find the path to a freer, more fulfilling adaptive lifestyle.

Principle 1 Of Active Change: Values Clarification

Today’s blog is about actively engaging in values clarification. Values clarification involves reflecting on questions such as: What is truly important to you? What moral/ethical/religious system guides your life? How do you make meaning out of the world? What do you really enjoy? What truly nourishes your soul? How do you do what you can to live more in accordance with your values?

Let’s acknowledge that these questions are hard to think about when you are depressed. They take mental energy, which is in short supply. In addition, they might make you start to feel negative feelings because such questions might start to remind you that your life is not where you hoped it would be. Thus, let’s acknowledge that maybe a part of you wants to turn away from this.

However, we should then pause and see that as part of the pattern of the shutdown. You get triggered, you get a jolt of negative pain, and then you move to avoid and escape. This “Trigger Response to pain Avoidance Pattern” is called a “TRAP”, and it is part of what drives folks to shut down. In the next blog, we will get into TRAPs and understand more directly how to avoid them and stay actively engaged.

Today, though, we are interested in values. So, let’s give you a chance to lean in. Here is a 6-minute video on Values Clarification by Dr. Richard Harvey that has some good information. At the very least, take the time to watch that and reflect on it. Ideally, that will lead to you taking the time and doing something more active.

Related: Which Eastern Religion Matches Closest To Your Values? Quiz

For example, here is an exercise on values clarification from Smart Recovery that might be useful. If you are interested in a longer, workbook format, here is a link to worksheets from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which is a therapy program and philosophy I find to be quite effective and that overlaps greatly with the view that guides this blog series. Another option is to Google “values clarification” for yourself and sees what pops up.

Today or in the next couple of days, please engage in some form of values clarification and start to think about how you might move yourself toward more adaptive living.

What follows over the next seven entries are seven more key principles for living with depression and for moving toward more adaptive living. They will center on the following domains:

1. Fostering activation and engagement instead of avoidance and shutdown

2. Developing “anti-depressant” habits and lifestyles

3. Fostering a healthy biology

4. Understanding how to engage in the adaptive processing of emotions

5. Developing positive ways of relating to others (and the model of others in your mind)

6. Engaging in more effective ways of thinking adaptively

7. Developing a mindful way of living that fosters growth and adaptive responses to stress

Notice that they are “principles” as opposed to “steps,” which was the language of the first half of the series. The reason is that each principle represents an area of adaptive focus. The blog series is designed to first help you with awareness and acceptance through a series of steps, and then give you tools to foster adaptive living in key areas via key principles. The principles are described and then resources in the form of books, links, and blogs are offered to guide you in furthering the principle in your life in a healthy way.

The word “healthy” here refers to engaging in processes that foster more adaptive living and valued states of being. It is attempting to be in a way that fills one’s souls and the souls of the people around them.

Be aware that each of the principles described below is relatively easy to state, but they are not easy to accomplish, for anyone. They are especially difficult when one is depressed. Consider that a number of them recommend books. Of course, reading books takes effort and time. That is the nature of the game we are playing.

Related: 30 Morning Affirmations To Boost Your Confidence Daily

If you are skeptical of books, be aware that systematic research has found that when folks are in the right stage of change, good books can be very effective in helping guide people out of depressive caves (see here and here for literature reviews demonstrating positive effects that are as strong or almost as strong as psychotherapy or other treatments considered effective).

As has been noted several times in this series, the journey outside the cave of depression can be a long one, and it takes effort and practice. That is true of each of these principles. They are offered for you to consider and they represent some of the ideas that professionals have developed that have good logic and have been shown to work.

However, they only “work” when the individual approaches them with a mindset that is open and oriented toward investing and learning more. Each “principle” can be adopted as the primary focus for one’s attitude and emphasis for change, or you can try to engage in several.

In getting prepared to take more action, I would also like you to remember the “beast” metaphor from the first blog. These principles are not about “forcing” depression out of you (i.e., winning a tug of war and dragging it into the pit).

Rather, each principle involves “seeing” that the beast of depression is there and working to move toward adaptive ways of being even as one experiences its burden. As noted by Acceptance and Commitment therapists, it is possible to both accept the pain one is in and commit to work toward valued goal states.

In the next step in this guide we will explore the core principle of activation and recommend principles for fostering adaptive engagement.

Step 9 : Behavioral Activation (BA)

BA is about deliberately working toward ways you can reverse cycles of avoidance and become more positively engaged in the world around you. This likely sounds pretty obvious (which in some ways it is), but we should note it is not necessarily easy to do. In step 8, we mentioned a way to frame the pattern of shutdown via the acronym “T R A P”, which is an acronym for Trigger, Response, and Avoidance Pattern. We want to avoid TRAPs and engage in positive activation.

Let me translate what this means: A stressor (either outside your head like someone criticizing you, or inside your head, like a scary thought or image) hits your consciousness. That “trigger” results in a painful “response” and that gets you to act via an “avoidance pattern” to be safe. An example can help illustrate what I mean: Joan wakes up and starts imagining her day and thinks about going to work and then being criticized by her boss about something she did. This image becomes a “Trigger” and the emotional “Response” in Joan’s head is a jolt of fear, pain, and resentment.

That makes her want to hide and stay in bed, which is the “Avoidance Pattern”. It is a classic depressive TRAP. To see why let’s play it out. If Joan responds this way, what will the consequence be? If she calls in sick and then lies in bed, where is she but sitting in the cave of depression? Not only that, she still has to wonder if her boss is going to critique her and now she has missed more time from work, so she is further behind.

And it would be likely that she now feels ineffective and has nothing productive to do. That is the nightmare of depressive cycles. The spiral you into the cave. Via avoidance, Joan tried to escape the pain. But her instinct to avoid actually caused her to jump out of the pan and right into the fire.

Related: Understanding your Emotional Command Systems

What should Joan have done?

Ideally, she would have mindfully “held” her feelings, then she would have worked to think things through constructively, and then she would have guided herself to act in a way that was consistent with BA.

In future blogs, we will explore how to think adaptively and mindfully hold one’s feelings. Today our focus is on diving into BA. At its core, BA is about deliberately working to construct one’s way of being in the world that increases engagement, pleasure, and productivity. Over time, this produces what is called a “virtuous growth cycle,” as opposed to the destructive cycle of a shutdown.

More specifically, BA is about finding pathways of positive investment that:

(a) move a person toward specific goals and thus more valued ways of being;

(b) result in mastery, competence, or achievement and the experience of growing and learning; and/or

(c) are pleasurable or entertaining. For a depressed individual, this may well sound both simple and unhelpful.

I can hear folks responding with the thought: “If my life was like that, then I would not be depressed!” We can acknowledge this initial negative reaction. In holding it, it does not follow that we need to give in to the avoidance pattern that follows from it (i.e., the conclusion being that there is nothing that can be done). Instead, the philosophy of BA is an attitude that fosters working toward positive investment.

How does one actually do this? There are many guides for how to accomplish this. Here is a good presentation on the basics of Behavioral Activation. I recommend you spend some time with it (or something similar–feel free to Google “behavioral activation” and look around). As is noted in the guide, BA includes a number of elements, such as

1) Understanding the “vicious cycles” of depression;

2) Identifying goals and values;

3) Monitoring daily activities;

4) Building an upward spiral of motivation and energy through pleasure and mastery;

5) Activity Scheduling;

6) Problem-solving around potential barriers to activation;

7) Working to reverse TRAPs, and

8) Maintaining an attitude that fosters learning and growth.

The guide also includes a detailed description of things like goals, values, mastery, and pleasure, ways to engage in activity scheduling, and ways to identify your core values and goals. It also provides lists of the kinds of activities that many people who are depressed find pleasurable. And it suggests ways to “experiment,” and see which ones are the best for you.

Let me add a few things to the model of BA that they offer.

Model of Behavioral Activation

First, let me note what I call the problem of initiation.

One of the things depressed moods do is “kill” behavioral initiation. This means that, for many depressed folks, it is really hard to get started on new activities. If you are one of these people, I encourage you to employ what I call the five-minute rule.

This is when you make an agreement with yourself that you do the activity for five minutes. Once folks get started and past the initial “inertia” of the shutdown, then they find that the activity takes on a better emotional tone. For example, I am not a huge fan of exercising. And, often, on my ride home from work, a little voice inside my head invites me to keep on driving past the gym, often with some excuse, like it has been a stressful day. My reply to myself is often something like, “Yes, I do feel like crap today for good reason.

So, I will go to the gym and start my workout. If, after five minutes, I still feel like crap, then I will give myself permission to head out.” Usually, five minutes into my workout, I am in a different place and it is much easier to finish it up and by the time I am done, I am glad I did it and feel a sense of accomplishment.

The second idea I would offer is what I call the pay it forward principle.

This refers to the fact that your future self will benefit if you are able to manage to engage in constructive action. Recall the example of Joan. Because she did not deal with the problem, her “future self” now had more problems to deal with. This means hard things built up.

If she had gotten out of bed, and faced the situation effectively–even if she felt miserable during that day–she likely would have woken up the next morning feeling as though she accomplished something. If you have a productive day even if you are not feeling it when it is happening, your future self will likely feel it–just as if you have an unproductive day, your future self will feel that in the opposite way.

I also recommend that in your work on fostering greater BA, try to be clear as to why you are doing what you are doing in terms of your values. For example, if you are cleaning your room, focus on the goal and the fact that doing it moves you to a valued outcome, rather than the thought that you hate dusting or doing laundry. It might help if you think of this as a kind of “behavioral engineering”. You are working to act in your daily life so that it is more engaging, rewarding and leads to greater levels of mastery, goal accomplishment, and pleasure.

In the next blog, we continue with this theme of BA, only there we will focus more on how to construct healthy daily habits and lifestyles. One way to bridge this blog to the next one is to focus on activity scheduling. Activity scheduling refers to the way you plan out what you are doing. I recommend a weekly planner that gives a basic structure to the week. I also recommend a daily planner.

The daily planner is something you do either in the morning when you get up or the night before. It lists the basic tasks and activities for the day. So, today, when I got up, I generated my task list, which included finishing and posting this blog, doing laundry, mowing the lawn, and taking my car to get its oil changed.

It is hard for me to overstate how important BA is to reversing depressive cycles. A good case can be made that BA has more scientific support for treating depressive conditions than any other principle. Of course, if we consider depression as a state of behavioral shutdown, the logic makes good sense. We must also note here that to be successful in employing BA, you will need to learn it and practice it and grow from it.

Related: Why We Need To Be Curious About Mental Illness

As with all the principles that follow, this takes time and effort. And it involves learning at the levels of a) thinking and understanding (i.e., knowing what shutdown and activation are at deeper levels); b) feeling (feeling both the shutdown and the hope and commitment to try to reverse it and feeling the consequences of both), and c) doing (genuinely trying new things and learning from them and adjusting and working to find what is rewarding for you).

This all takes time. This blog gives an outline, but I recommend you seriously “sit” with these ideas and consider really committing to them. To do so you need to immerse yourself in them. There are several excellent books that guide you through this “BA engineering” process. Two such books are:

We have now covered two core principles of Active change. In the previous blog, we covered values clarification and here that of BA. In the step 10, we expand the BAprinciple from a general way of responding to a way of cultivating a particular kind of lifestyle. I look forward to continuing on this journey with you.

Step 10: Healthy Lifestyles

Our primary guide for this part of the blog series is the work by Dr. Steve Iliardi and his excellent book called The Depression Cure (here is a pdf). It starts with the argument that there is a depression epidemic that is spreading, and the likely reason is because our lifestyles. He reviews research findings that suggest that people who life more traditional indigenous hunter-gatherer type lifestyles are much less likely to get depressed. He writes:

Modern-day hunter-gatherer bands—such as the Kaluli people of the New Guinea highlands—have been assessed by Western researchers for the presence of mental illness. Remarkably, clinical depression is almost completely nonexistent among such groups, whose way of life is similar to that of our remote ancestors.

Despite living very hard lives—with none of the material comforts or medical advances we take for granted—they’re largely immune to the plague of depressive illness that we see ruining lives all around us. In perhaps the most telling example, anthropologist Edward Schieffelin lived among the Kaluli for nearly a decade and carefully interviewed over two thousand men, women, and children regarding their experience of grief and depression; he found only one person who came close to meeting our full diagnostic criteria for depressive illness.

What is going on here?

One strong line of thinking is called the “evolutionary mismatch” argument. It refers to the fact that there is a contrast between our current lifestyles and the environment our minds and bodies evolved to live in. Consider, for example, a likely reason we experience tooth decay is that we eat very different kinds of foods than our ancestors.

The same may apply to depression. The lives of our ancestors were, like the Kaluli peoples, close-knit hunter-gather tribes that would live and work together to meet the challenges of survival and reproduction in natural environments. In contrast, we live in a highly fractured, complicated, stressful, high-paced life. Moreover, we can become easily socially isolated in ways that our ancestors would not. This huge difference likely creates lots of problems with our biological and mental health and it provides a good way to understand the modern epidemic of depression.

Dr. Ilardi’s book details a Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (TLC) program that systematically reviews key domains of living and guides the reader in developing healthy, “anti-depressant” habits in each. This is a well-researched program found the following: “Patients were randomly assigned to receive either TLC or treatment-as-usual in the community (mostly medication), and fewer than 25% of those in community-based treatment got better. But the response rate among TLC patients was over three times higher.

In fact, every single patient who put the full program into practice got better, even though most had already failed to get well on antidepressant medications.” The reviews the book receives are generally outstanding. As such, it serves as our guide for today’s key adaptive principle, which is cultivating an adaptive lifestyle.

Six Key Lifestyle Domains

The TLC program identifies six key lifestyle domains, each of which represent areas that our ancestors engaged in dramatically different ways of being than we do.

1. The first domain he identifies is dietary, specifically the consumption of omega 3 fatty acids.

He notes how crucial such fatty acids are for brain function and that hunter gatherers ate much more fatty acid rich foods than we tend to do. He offers a systematic way to monitor and change one’s diet to increase fatty acid consumption.

Related: 6 Ways Food Impacts Your Mental Health

2. The second domain is exercise.

Noting that hunter-gatherers were in much better shape than we are, he encourages physical exercise. I would especially encourage folks to consider walking. Walking with a friend or walking in nature or walking while you listen to music or a podcast on a topic you are fascinated by is a great way to get exercise and also make connections and be outside and learn new things.

3. Productive engagement

Much as our previous blog, Dr. Ilardi emphasizes the need for productive engagement with various activities and explores ways to foster such engagement in one’s life.

4. Sunlight exposure

We spend much of our time indoors and are exposed to natural sunlight much less than our ancestors. We know that light therapy is important for bipolar conditions and Dr. Ilardi argues that sunlight exposure is helpful for our bodies and minds to feel alive and engaged. The book recommends increasing sunlight exposure and provides clever ways to accomplish that.

5. Social support and connection is the fifth lifestyle.

In a future blog entry, I will be discussing the importance of relationships and feeling secure and known and valued by others. Here we can note the importance of human connection and the book examines ways one might increase connection with others. For example, one might join a club or a church or invite a friend to become a regular walking partner.

Related: How Emotional Support Animals can Help with Mental Health

6. Sleep

Sleep is one of our most important habits and a regular and fulfilling sleep pattern is crucial for our health. The book explores good sleep hygiene and offers suggestions for getting a good night’s sleep.