There are so many people in this world who suffer from irrational guilt over things that were completely out of their control. It’s a heavy burden to carry and if you are one of them, then know that you are not alone. Living with irrational guilt is heartbreaking, but overcoming irrational guilt is not as impossible as it may seem.

KEY POINTS:

- Many people suffer from irrational guilt, blaming themselves for things over which they had no control.

- The guilt is based on the conviction that they had the power to control a terrible event or situation.

- Self-forgiveness requires giving up illusion of omnipotence.

The new film “One Life” depicts Nicholas Winton’s visit to Prague in December 1938 and January 1939, shortly before Nazi takeover of all of Czechoslovakia. He coordinated with humanitarians like Trevor Chadwick, Martin Blake, and Doreen Warriner to identify hundreds of Jewish children who needed safe homes.

Upon his return to London, “Nicky” and his mother Babi Winton worked to procure the necessary paperwork, funding, and homes for the children. Around 6,000 people are estimated to be alive today due to the Wintons’ and others’ efforts in the Prague Rescue.

The last train that Winton and his team organized was supposed to leave Prague on September 1, 1939, but Germany invaded Poland and set off World War II. The Nazis did not allow the train to leave Prague.

From the point of view of a psychoanalyst, the movie is about irrational guilt and the difficulty of forgiving oneself for something one has no control over. Winton saved almost 700 children, but he could not save the ones on that last train.

Related: A 5-Step Guide To Escape The Guilt Trap

This Is What Irrational Guilt Looks Like

The BBC talk show “That’s Life” orchestrated a 1988 meeting between him and dozens of the “children” he saved. The movie implies that Winton was obsessed with the loss of the last train, and it was intrusive in his life.

He hoarded every file and document related to it. We see his wife chiding him for all the old boxes that fill his office. Winton piles old typewriters and anything that “might be useful” in his living room to give to people who might need it. Despite his wife’s pleas to “let it go,” he was still grappling with his guilt; he could not forgive himself.

Many people suffer from irrational guilt, blaming themselves for things over which they had no control. For example, my patient Catherine feels guilty because her mother suffered a vaginal tear during childbirth from which she never fully recovered. In Catherine’s case, her mother kept blaming her for it.

Patricia blames herself for her father sexually abusing her sister; Sal can’t forgive himself for his father’s physical abuse of his mother; and Kenneth blames himself for his mother’s suicide. In these cases, they were children and had no control over what their fathers did. Yet they cannot forgive themselves.

What I have come to understand is that their guilt is related to a sense of power. Patricia, Sal, and Kenneth have a conviction that they had the power to intervene. To forgive themselves, they would have to give up their sense of control; they would have to accept their powerlessness. Horrible things happen and we have no control over them, especially if we are children.

Winton lived to be 106. Of course, I do not know if he was able to forgive himself after he met some of the grown-up children he had saved. He must have had a conviction that he was powerful to devote himself to saving Prague’s Jewish children.

Related: Healing From Within: 10 Tips To Forgive Yourself For Past Mistakes

His conviction about his own power spurred him to organize a huge humanitarian effort, but when he was not 100 percent successful, he could not forgive himself. He felt he should have been able to save every child.

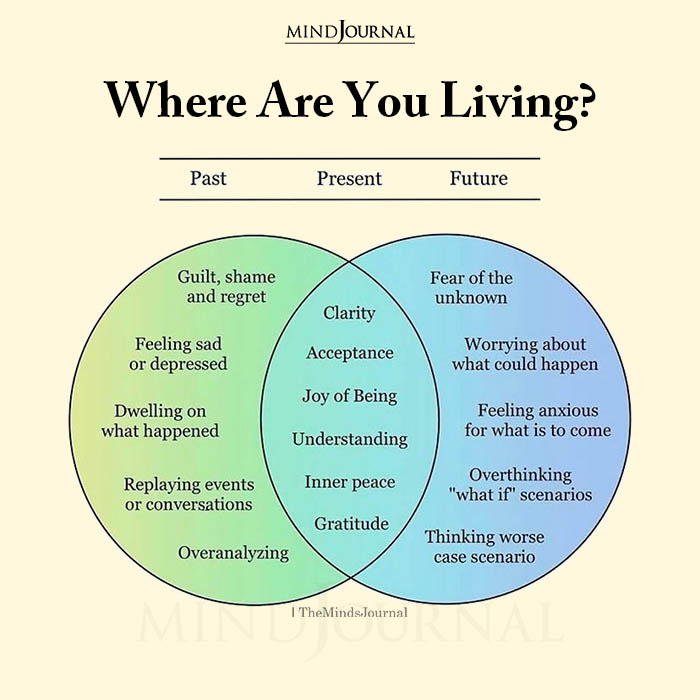

Overcoming irrational guilt requires accepting the limits of your power.

Want to know more about living with irrational guilt? Check this video out below!

Check out an excerpt from Roberta Satow’s book, Our Time Is Up here:

“The weather in our house was stormy with the promise of thunder and lightning. I walked on the balls of my feet, as if to prepare for the thunderclaps that would slam me across the room. Before I started elementary school, I was alone with my mother when my father left for work at the Hunter Coal Company on Flatbush Avenue.

As usual on Wednesdays, she put on her shmata, a sleeveless cotton housedress that tied across the front. The pink and green flowers on the dress accentuated the scowl on her face. She hated cleaning. But it was her life sentence. She filled a brown plastic bucket with hot water and added Ivory soap flakes and Jane Parker ammonia.

Putting on her yellow plastic gloves to protect her nail polish, she dropped the wooden brush with stiff bristles into the bucket. Then she turned to me and said, “Go out on the porch so I can wash the floor.”

She ushered me down the narrow hall with her gloved hand on the small of my back, and shut the door behind me. Once exiled, peering through the glass panes in the front door, I watched her on her hands and knees scrubbing the linoleum floor.

Her breasts peeked out of her shmata with each forward movement of the brush, and an occasional smile crossed her face as she listened to Rayburn and Finch on the radio.

Outside, the trees tossed in the wind and clouds scudded across the sky. The porch shook from the elevated train that stopped half a block from our house on its way to Coney Island. At the foot of the concrete steps, there were three large dogs—a dirty German shepherd, a dark gray mutt with a wrinkled face and a black snout, and a long-haired white mongrel.

They lived in an empty lot on McDonald Avenue around the corner from our house, and roamed the streets looking for food early each morning. Saliva dripped from the German shepherd’s mouth as he bared his teeth and snarled.

I ran back to the front door. “Ma, Ma the dogs are out here! Let me in! Please, Ma!” I pleaded.

“Be quiet,” she yelled, red-faced with sweat dripping, “and wait on the porch!” I whimpered, “Mommy please, I’m scared of the dogs. . . . ”

The white mongrel growled. I pulled one of the rusted metal chairs as far from the stoop and the dogs as I could get it and crouched behind it. I watched the dogs at the bottom of the stairs jumping up on each other and barking loudly.

They could run up the steps at any moment and I would be cornered. Then I imagined there was an invisible fence at the steps, but it only worked if I kept my eyes firmly fixed on the dogs. I stared at the dogs and chanted, “A hundred bottles of beer on the wall, a hundred bottles of beer, take one down and pass it around, ninety-nine bottles of beer. . . .”

When my mother finished, she poured the brown sudsy water in the kitchen sink, rinsed the bucket and brush, carefully turned the brush upside down to air dry, untied her shmata, andturned on the faucet for her bath. I heard the water running.

The dogs moved on down the block and the terror passed. I stood up and sat in the chair, breathing heavily and staring into space. She did not come out to get me when she was finished. She just took her bath and went to lie down on her bed.

I could see her pull down the quilted bedspread as I stood on my tiptoes peering through her bedroom window that faced the porch. It was safe to go back in the house. The floor must already be dry, but I had to be quiet. I was crossing a mine field and had to hold my breath, tiptoe slowly, and not jostle anything.

Opening and closing the door could cause an explosion. I smelled the light citrus of Jean Nate toilet water as I passed the steamy bathroom on the way to my room. I closed the door carefully behind me and exhaled.”

Written By Roberta Satow

Originally Appeared On Psychology Today

Leave a Reply