Evolution provides some ways of understanding depression’s origins and impact. Most everyone has heard of “fight or flight” as an explanation for anxiety. It reflects the fact that animals when faced with danger either prepare to fight the thing that threatens them or run away from the thing that threatens.

In this way, animals are better able to survive against their enemies.

Humans face challenges different from animals out in the wild. They cannot typically fight what threatens them or run away from something causing them distress. If you feel threatened by something at work, you can’t just start a fight with your boss or run away from your job.

No Option To Run Away From Problems

Anxiety in humans develops because they are often stuck with not being able to do what they most naturally want to do. So, an employee who can’t run away or start a fight with her or his boss starts to worry because of being unable to respond how he or she most naturally wants to respond. Evolution led to animals wanting to run away or fight when facing challenges so having to find another option causes symptoms of anxiety. How long that anxiety lasts depends on how long it takes for the person to decide on and use another option.

“Fight or flight” describes how a mechanism that helps with survival in animals impacts humans when they cannot respond that way. It shows how an evolutionary process can cause difficulties for humans when they do not find alternative ways of dealing with threats.

Read Ekman’s 6 Basic Emotions and How They Affect Our Behavior

Anxiety, as a biological process, is rather easy to understand when the thought of in terms of “fight or flight”. There actually is a similar survival instinct in animals that helps to explain depression. It is called “social competition theory”.

Animals often fight to achieve some level of dominance in their group. Hierarchies are important for many animal species and being higher up in a group hierarchy can represent opportunities for more food, better access to resources, and, most important for evolution, more opportunities to reproduce.

Fighting for a higher spot in your group presents a lot of opportunities for animals. But it also presents a lot of dangers. “Fight to the death” is not just a cliché with many animal species but often represents a real way that conflicts are decided. An animal who decides to challenge another animal for a higher spot in a group runs a real chance of getting hurt in the process.

So, in order for an animal to survive, “giving up” in a fight can be a really useful strategy. If an animal thinks that a potential opponent could seriously hurt them in a fight, it is in their best interest to show as clearly as possible that they are not challenging their potential opponent. All sorts of signals, including lowering the head and backing away, show clearly to one animal when another animal has no interest in having any sort of competition. In this way, the outcome of a challenge is decided without either of the animals having any risk of being harmed or killed.

Certainly, one way to look at this is that this response to “social competition” prevents one animal from facing serious harm or death when facing an opponent she or he sees as stronger or otherwise likely to win a competition. But it also relates to animals not wasting energy in challenges at which they are not likely to succeed.

Read How I Healed My Life-Long Anxiety

Learned Helplessness

“Giving up” in situations where an individual is not likely to succeed is known as “learned helplessness”. Animals show “learned helplessness” in situations where challenges are insurmountable (or at least seem insurmountable to the animal). This could include situations where animals feel pain or discomfort in settings they cannot escape.

Very often animals caught in these situations will eventually stop trying to leave and will just stop and not move. They very much make clear that they have “given up” in these situations. “Giving up” is preferable to wasting energy or other resources trying to escape a situation that the animal perceives cannot be escaped.

“Learned helplessness” exists as a natural response in animals meant to aid in survival. It has been found as a construct even at the genetic level. Certain types of rats and mice are chosen for studies of “learned helplessness” because they have this specific type of genetic makeup. Having a genetic predisposition to experience “learned helplessness” quicker than others can be one way of thinking of the types of genetic factors contributing to a higher likelihood of developing depression.

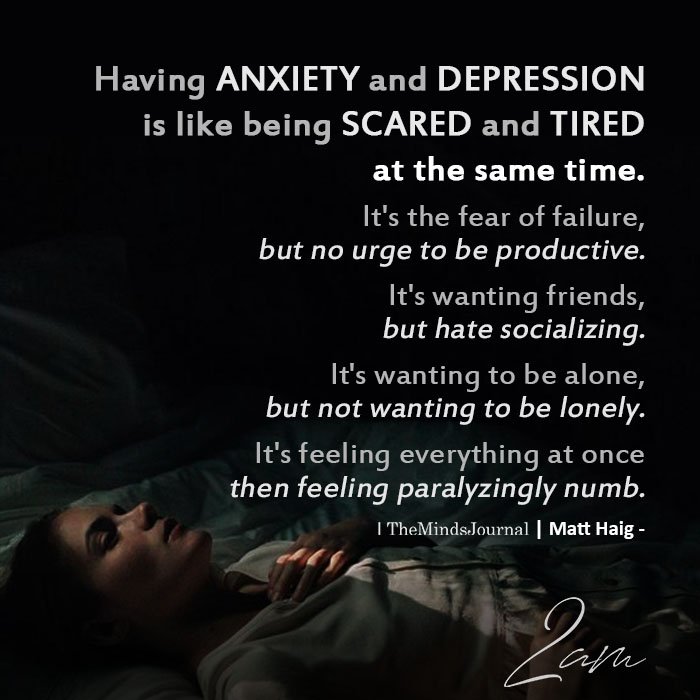

Clinical depression looks very similar to the presentation of animals who have “given up” when facing competitions or challenges. There is a withdrawal from the immediate environment, a decrease in motivation, and looks of defeat. Intense feelings of sadness and loss, common in individuals suffering defeat, are also characteristic of depression.

Read What Is Learned Helplessness And How It’s Connected To Trauma

Humans who suffer depression also often refer to themselves as feeling “defeated” or feeling “there’s just no point in even trying”. Those would be verbal descriptions of what is actually happening on an instinctual level for someone suffering “learned helplessness”. It would also reflect verbally what happens to an individual on the losing end of social competition. “Social competition” theory has been used to explain many different types of depression.

Social Competition

One recent article (Blease, 2015) applies this theory to a type of depression called “Facebook depression”. There is considerable evidence that many individuals who use Facebook frequently suffer from depression.

One possible reason put forth by this author is that many Facebook users brag in their posts. There is more of a tendency on Facebook to stress and often exaggerate accomplishments. This can heighten social competition infrequent Facebook users, especially those users who are subjected more often to “bragging posts”, and can increase the likelihood of depression when users do not feel they match up to what others are accomplishing.

All of this does not mean that depression is simply a matter of people feeling like they can’t win one fight or accomplish one specific goal. It is not a reflection of just not reaching a goal and feeling bad about it. It goes much deeper than that. In fact, looking at depression as related to evolutionary processes developed for survival can help explain why it is such an all-encompassing type of problem.

Animals trying to avoid potentially dangerous competitions cannot just “give up in one moment and then move on with their lives. It is a response that lasts and that has to last for the animals’ very survival. Otherwise, the animal risks finding themselves in danger of facing that competition again.

People with clinical depression do not typically describe themselves as just feeling like they “lost one battle” and “failed at one task” when describing how they feel. But they do often describe themselves as feeling they are a “loser” or a “failure”. They also often describe themselves as feeling “defeated by life” or being “unable to accomplish anything meaningful”.

Read 7 Big, Stupid, Destructive Lies Depression Tells You

Looking at that as a response to just one or two negative events does not help explain such all-encompassing descriptions. But looking at depression as related to an evolutionary process, developed for an animal’s very survival, reflects one way of understanding why it can feel so all-encompassing and so pervasive.

Not that having successes, and recognizing those successes, can’t help. One of the problems with depression is not that sufferers don’t have successes; they do, but more that they don’t recognize them or really process them. Depression, again because of its relation to response animals need for survival, frequently involves an intense focus on loss and surrender.

Changing that focus to one processing accomplishments and successes effectively can be very difficult but helpful. It is not a matter of seeing everything as a positive but more of a change where everything does not seem like a negative. That is essentially the main focus of cognitive-behavior therapy, one of the most effective types of treatment for clinical depression.

Looking at clinical depression as linked to biological processes and survival instincts evolving over centuries does not explain all aspects of this serious condition. But it can help explain at least some of why it can be so devastating and offer at least some hope and direction for support and treatment. Much like the “fight or flight” response, it offers a very basic way of understanding where depression comes from and why it has such a strong impact.

References Blease, C. R. (2015). Too many ‘friends,’too few ‘likes’? Evolutionary psychology and ‘Facebook depression’. Review of General Psychology, 19(1), 1-13.

Written by: Dr. Daniel Marston Originally appeared on: Psychology Today Republished with permission

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most obvious sign of clinical depression?

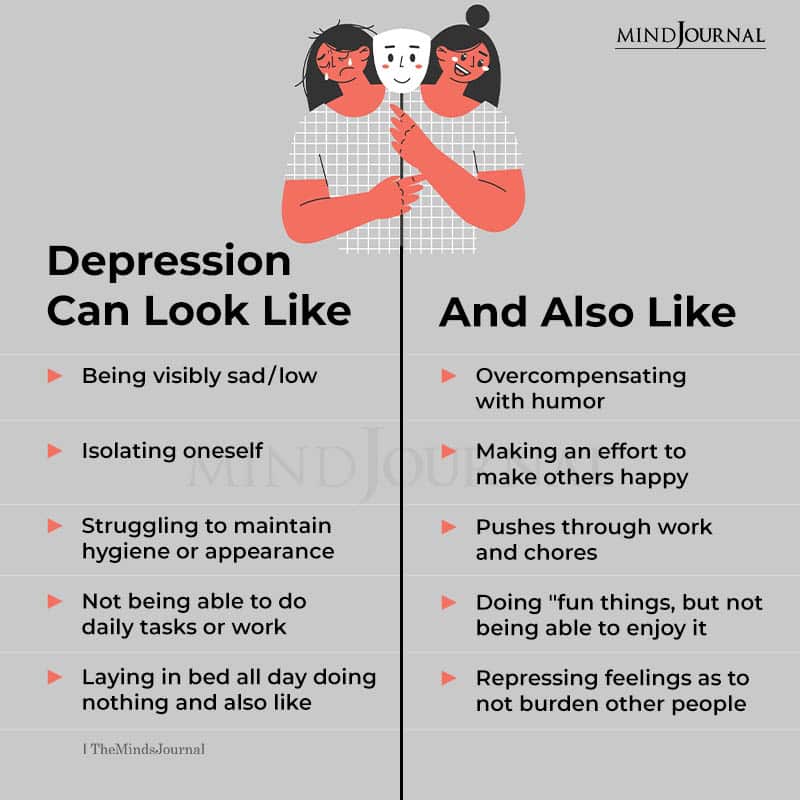

Although only a mental health expert can diagnose clinical depression, some signs to look out for are, perpetual sadness, emptiness, fatigue, tearfulness, hopelessness, irritability, frequent outbursts, and loss of interest.

Why is it so hard to talk or text back when I’m having a depressive episode?

Depression can strip you of your energy and willingness to be functional. It can bring forth fatigue, hopelessness, and a loss of purpose. It’s normal to lose interest or pleasure in normal activities such as maintaining contact with loved ones.

Why is it important to talk to someone about depression and other mental health issues?

Talking about mental health challenges can be a key factor in recovery. Patients feel much better after opening up about their issues either to a medical professional or a loved one. It also brings awareness to the subject.

Leave a Reply